(This content is not original, it is heavily inspired by the page Swungover, created and maintained by Bobby White. We are not historians: the following statements should be taken with a grain of salt.)

Willa Mae Ricker and Leon James: photoshoot for LIFE magazine.

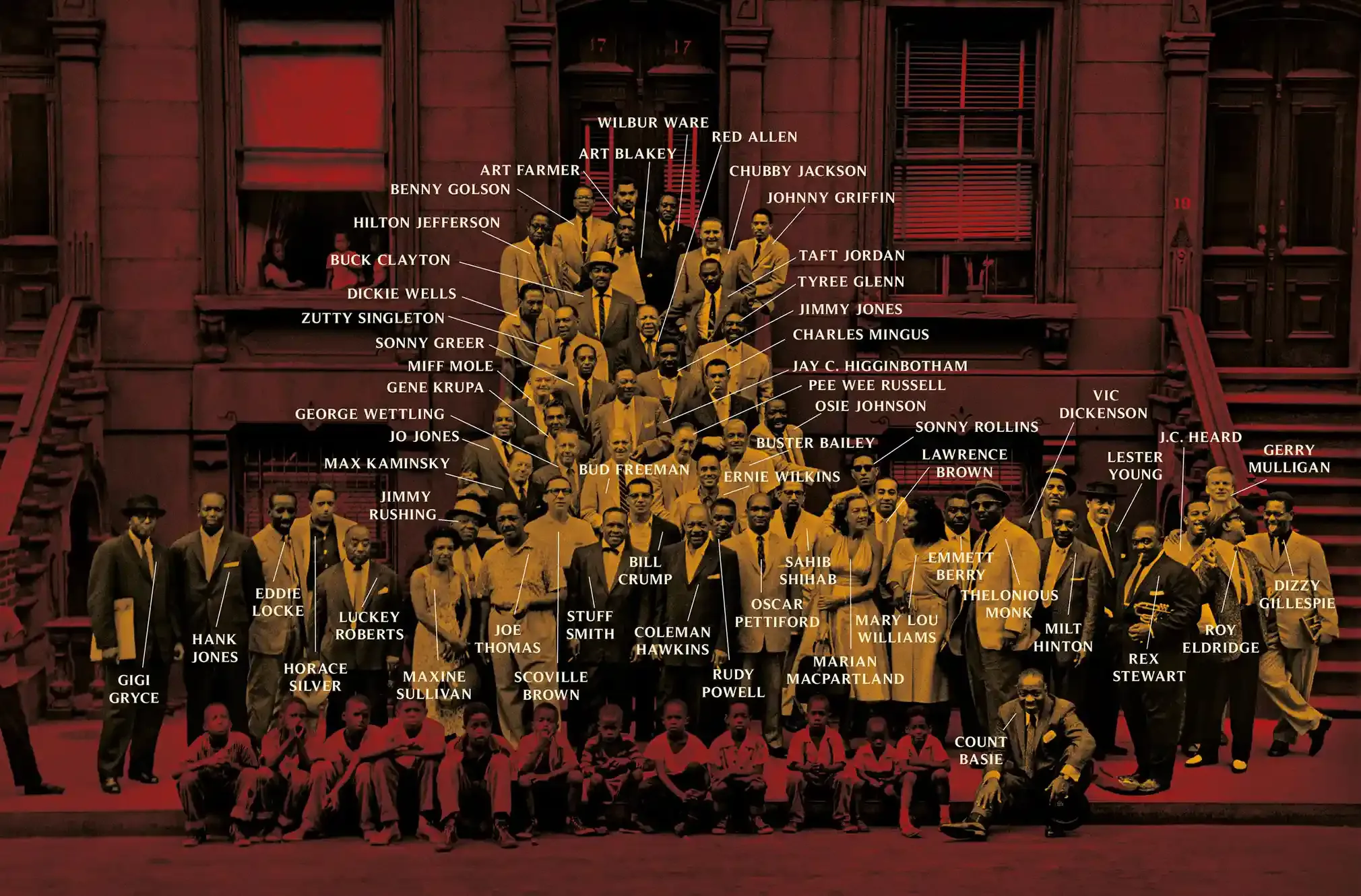

Four generations of jazz musicians, captured by Art Kane in 1958. More information about this photoshoot here.

Like many popular social dances, the history of Lindy Hop is inseparable from the history of the music it is danced to. The jazz of the late 1920s, then the 1930s, and finally the first part of the 1940s (i.e., swing) is the alpha and omega of Lindy Hop. It gives it its particular groove, its way of conceiving the relationship between partners, as well as its energy, both joyful and profound.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, the black and Creole communities of New Orleans gave birth to several musical forms that had a great influence on American popular culture (e.g., ragtime and emerging “hot jazz”). Both locally and nationally, these different music styles were quickly accompanied by dances that revolved around their particular energies.

Thus, in the mid-1920s, when the “Jazz Age” was consolidating, the United States was swept by its first national dance craze: the Charleston. It was a dance - first solo, then partnered - that originated in the city of the same name. Its most characteristic features (for example: the twisting of the feet, resulting from a rotation of the femoral neck) are reminiscent - according to some researchers - of West African dances. This is hardly surprising: indeed, the port of Charleston was one of the main arrival points in the United States for enslaved people coming from, precisely, West Africa.

But the Charleston was not the only African-American dance to sweep across the United States in the early twentieth century. Between the 1910s and 1940s, there were dozens of such dance crazes. At the end of the 1920s, for example, in the Harlem neighborhood of New York, there were at least three different partner dances practiced in the clubs: the Harlem version of Charleston, the “Breakaway,” and a third dance about which little is known, called “Collegiate.”

The “Breakaway” included many movements derived from the Charleston danced in couple, making the two dances sometimes difficult to differentiate. But the Breakaway also contained a characteristic dynamic, to which it owed its name, and of crucial importance for the future development of the Lindy Hop: during a few musical beats (« beats » in English), the dancers abandoned the closed position – while remaining connected by at least one hand – before finding themselves again in each other’s arms. This momentary opening of space between the dancers constituted a real innovation, as well as a redefinition of the couple dance. In particular, it created the possibility of a couple dance in which the partners would maintain a relationship analogous to that of the musicians of a jazz group: together and interdependent thanks to listening and shared structures, and yet free to express their voices in all their individualities. The Lindy Hop is this possibility that is realized.

During the decade of the 1930s, Harlem (a New York neighborhood, located above Central Park), became the cradle and center of a new sound, a new manifestation of jazz: the swing.

Harlem was a predominantly black neighborhood, even though it also contained strong Italian and Hispanic communities. In the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance had converted this neighborhood into a kind of haven of hope for blacks (Americans, but also beyond, as reflected in the beginning of Norma Miller’s biography). The Great Depression (1929) struck this neighborhood with a particular severity; but despite imposing extremely harsh living conditions on its inhabitants, it did not prevent the development of swing, whose joyful and infectious beat helped to resist adversity.

Clubs and theaters, often equipped with jazz ensembles in residence, multiplied in the Harlem neighborhood, which thus became a cultural center – for the Harlemites, but also for the rest of the city, as well as for tourists visiting New York. The unpleasant side of this phenomenon are the clubs like the famous “Cotton Club” which exhibit the wonders of an African-American culture in full boil for an exclusively white clientele. But not all clubs had this operating mode: Small’s Paradise (one of the first reputed clubs whose owner was an African-American) and, later, the Savoy Ballroom did not segregate their clientele (at least not on racial criteria: it seems that the prices of Small’s Paradise were too prohibitive for an average Harlemite salary). It is in this Harlem bubbling with injustice, struggles, creativity and resilience that the Lindy Hop was born. It is from this Harlem cultural center in New York and the United States that it became a fashion phenomenon and spread throughout the country, then throughout the world.

If there is one club that, more than any other, is associated with the birth and development of the Lindy Hop and Swing, it is the Savoy Ballroom. Located at the intersection of the 141st Street and the 7th Avenue, it was one of the largest clubs in the area: it occupied an entire block of buildings. A large sign above the entrance indicated that one was dealing with the house of happy feet (« Home of the Happy Feet »). Opened in 1926, the Savoy Ballroom was one of the first integrated dance halls (i.e. that did not practice segregation). It quickly became the ultimate nightclub for Harlemites. A place of creation or consecration of new trends in African-American music and dance.

It was thus, from the stage of the Savoy, that a drummer of very small stature, suffering from an osteo-pulmonary tuberculosis which made him bow and took away his life before he even reached the age of 40, dedicated himself as the first « King of Swing ». His name was not other than Chick Webb – genius percussionist, energetic animator, and one of the fathers of the swinging rhythmic sections. Chick Webb was the leader of the resident jazz ensemble at the Savoy Ballroom from 1931 and almost until his death in 1939. During his 8 years of activity at the Savoy Ballroom, he won an innumerable number of « Battles of the Bands », discovered the young Ella Fitzgerald and nourished the creativity of the first generations of Lindy Hoppers.

Of the few names that are associated with the first generation of Lindy Hoppers (« Twisted Mouth » George, Big Bea, Mattie Purnell and « Shorty » George), it is that of Shorty George who occupies the most place. According to several sources, he greatly contributed to the creation and development of the Lindy Hop. It is also probably the first person to form a Lindy Hop troupe in order to make exhibitions and shows. Moreover, his troupe was the first Lindy Hop troupe to appear in a film. Finally, it is Shorty George who would have baptized the Lindy. During a marathon dance, the story tells, a journalist approached Shorty George, asking him about the name of the dance he was executing so brilliantly, with his partner Mattie Purnell. Shorty, inspired by the big headlines of a newspaper which, in reference to the transatlantic flight of Charles Lindberg, titled « Lindy hops over the Atlantic », would have then replied that they were dancing the « Lindy Hop ».

But it is indeed the second great generation of Lindy Hoppers, organized around a named Herbert « Whitey » White who gave this dance its letters of nobility, and made it a national and soon international phenomenon. The actors of this second generation of Lindy Hoppers – who flourished and imposed themselves from the second half of the 1930s - are a group of African-American adolescents or young adults overflowing with talent, enthusiasm and energy, and who – under the name of « Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers » - won prestigious competitions (the famous « Harvest Moon Ball »), invaded the United States theaters, toured the world, and appeared in many films. These are, among others, Willa Mae Ricker, Leon James, Al Minns, Ann Johnson, Norma Miller and the inevitable Frankie Manning. If you have not yet seen them dance, watch them in « Hellzapoppin’ », « A Day At The Races » and « Keep Punchin’ ».

The “Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers” transformed the Lindy Hop profoundly, and gave it the form that made it an incredibly effective spectacle dance. They put in place the first group choreographies where the dancers perform movements in unison, highlighting certain elements of the music. They created the “Air-Steps”, these acrobatic movements where one of the partners jumps, performs a figure and lands in rhythm. And they wrote the choreographies – today often described as “Classic Routines” - around which the modern community of Lindy Hoppers gathers (the Shim Sham, the Tranky Doo, the Big Apple, and the California Routine).

The success of the “Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers” contributed to making the Lindy Hop a real mass phenomenon. Just as swing became, during the second half of the 1930s, the popular music of the United States, the Lindy Hop became the dance. Thus, it is indeed the Lindy Hop that the American soldiers took with them to Europe during the Second World War.

When we talk about the popularization of the Lindy Hop (and Swing) at the end of the 1930s, it is important to note that this popularization movement – both in music and in dance – was accompanied by the exclusion of African-American creators, who were replaced by white musicians (Benny Goodman succeeds Chick Webb as the “King of Swing”) and white dancers (in the dance scenes of the “Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers”, Dean Collins, Jewel McGowan and Jean Veloz take over the dance scenes). Thus, the story repeated itself once again, and the (main) economic and honorary benefits of African-American cultural products ended up in the hands of white people.

For many reasons, but mainly simply in response to the evolution of musical tastes, the Lindy Hop ceased to be the fashion dance after the Second World War. There is no doubt that many dances that came to impose themselves later (for example the Rock & Roll) share more than a resemblance (a real link of kinship) with the Lindy Hop.

Moreover, although it had no longer the same popularity, the Lindy Hop did not disappear. It was still practiced and shared in certain African-American communities. And the link of kinship between jazz dances and some more recent African-American dances (for example the Hip Hop) is so obvious, that it is sometimes tempting to think that Lindy Hop, Jazz, Funk, Hip Hop, are in fact different manifestations of a unique continuum - of an aesthetics and a way of thinking about the relationship between dance, music, the individual and the collective proper to the African-American community - which takes on different guises depending on the groove of the time.

From the 1980s, different organizations and people (Mama Lou Parks in New York, The Jiving Lindy Hoppers in Great Britain, and those who will become the Rhythm Hot Shots in Sweden) invest money, time and energy to repopularize the Lindy Hop. Their efforts bring some of the pioneers (especially Frankie Manning, but also Al Minns and Norma Miller, for example) to travel around the world and share the Lindy Hop with audiences from all over the world.

This movement is sometimes described as “revival”, a term that has been strongly criticized recently since, according to its detractors, it suggests that the Lindy Hop would have been abandoned by the African-American community and saved by dancers (mainly white), who would have rediscovered it.

Today, the Lindy Hop is a dance practiced on all continents. It is a living dance, in perpetual evolution; it is a dance charged with history; it is a liberating dance, joyful but not innocent; and this is how we want to transmit it to you.